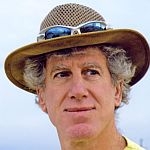

(HOST) Memorial Day wildfires triggered a memory of naturalist writer Ted Levin’s graduate school days and the ecological benefits of fire.

(HOST) Memorial Day wildfires triggered a memory of naturalist writer Ted Levin’s graduate school days and the ecological benefits of fire.

(LEVIN) In 1973, I took a graduate course in fire ecology taught on the Staked Plains of West Texas, what naturalists refer to as the "Llano Estacado, the flattest, driest, harshest corner of the North American grasslands" – land a raindrop away from desert. Whenever it rained, which wasn’t often, cowboys declared, "A cow’s pissing on a flat rock." The class lab was memorable. We burned 800 acres of tobosa grassland along the Prairie Dog Fork of the Brazos River.

Because the fuel load was low – grasses were barely six-inches tall – I jumped over the serpentine lines of fire that coiled and recoiled across my study plot.

Fire, I discovered, killed cactus and mesquite, invaders of the overgrazed plains, and stimulated the growth of grasses, which lushly sprouted from underground rhizomes a day or two after the burn. Hawks and vultures arrived out of a cloudless blue sky and coyotes and gray fox out of bottomland cottonwoods, lured by the promise of barbecued rodents and lubber grasshoppers.

Wildfire is a preeminent and well-understood ingredient in the grasslands all over the world. Though less obvious and far less frequent, fire has also influenced the Northwoods.

Seven o’clock Memorial Day morning, several hours before a schoolyard doubleheader, my neighbor Lynn called to see if our house or barn was burning. I stepped outside, smelled smoke, and noticed an acrid haze had transformed the air quality of Thetford Center to that of downtown Los Angeles. What I didn’t know at the time was that I was smelling lightning fires 250 miles away. As a chunk of central Quebec smoldered I wandered around the neighborhood, sniffing.

Wildfire in the boreal forest reverses plant succession and prepares a mineral seedbed on the thin soil surface. In fact, jack pine, which grows throughout the Great Lakes and St. Lawrence drainage (barely reaching into Vermont) is fire-dependent. Most cones remain on the pine for several years, and fire, which melts the resinous bonding material that seals the cone, releases the seeds. According to my old fire ecology notes, a temperature of 122 degrees Fahrenheit will do it. However, cones on the burning forest floor turn to ash.

Shortly after a fire, the airborne seeds and sprouts of aspen and balsam poplar reestablish these pioneer hardwoods and with them a litany of wildlife from moose to beaver to ruffed grouse that eat the bark, branches, leaves, and buds. Even Northwood old-growth species, like spruces and firs, have tiny wind-wafted seeds and soon reappear after a big burn. Fire favors blueberries, which flourish on the barren, sun-flooded ground, benefitting berry eaters: black bear, robin, thrushes, catbird, deer mouse, human – among many other species.

So, during Memorial Day doubleheader, when I stood in the third-base coach’s box rubbing the blue-gray haze from my eyes, I wasn’t giving the signal to steal second; I was thinking back to my days in graduate school, and to wildfire’s importance as an author of North American biomes.