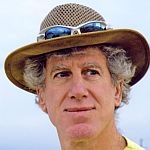

(HOST) On a recent vacation, nature writer and photographer Ted Levin took notice of ‘elemental life’ amidst extravagant American lifestyles.

(HOST) On a recent vacation, nature writer and photographer Ted Levin took notice of ‘elemental life’ amidst extravagant American lifestyles.

(LEVIN) When I think of Newport, Rhode Island I never think of clam worms. Tennis and yachts yes . . . and unadulterated wealth: there’s so much extravagance in Newport that the town’s carbon footprint is probably larger than many third-world countries, and the collective income of its summer residents may very well exceed the gross national product of Mexico.

So when my family recently traveled to Newport to vacation on a friend’s 65-foot yacht, I would have never guessed that when we returned home the thing we’d talk about most would be clam worms, which incidentally having nothing to do with clams. To be precise, we spoke about the sex life of one particular species, Dumeril’s clam worm, Platynereis dumerilii.

Clam worms are five to seven-inches long, segmented, and live on the muddy bottom of bays and estuaries from the Gulf of the St. Lawrence to Delaware Bay. Dumeril’s clam worm inhabits the lower intertidal zone to 400 feet deep among tufts of rockweed and patches of eelgrass. It also floats on seaweed and attaches to dock pilings.

When I was a boy on Long Island, clam worms were bait worms. We’d chop them up and fish for flounder or string them whole and fish for stripers. But until one moonlit night in Newport, I had never seen a worm swarm, a mating orgy of wiggly sexually active pieces of worms that zip across the surface of the sea like the little purple flashes of light you see behind your eyelids when you rub your eyes too hard.

A waxing summer moon triggers an adult clam worm to split into several highly mobile pieces, each with well-developed sexual organs. The wormettes swim to the surface, bathed in moonlight. They’re lured to the boat’s submerged taillights, like moths to a porch light.

Hundreds of them swirl around the surface, each inch-and-a-half long female attended by three to five smaller males. Eventually, the female grabs the hind-end of the closest male and ingests his sperm, which perforates an interior wall, and fertilizes her eggs. Then, the eggs burst through the female’s deteriorating body, a silent procreational puff of white. The female’s wispy carcass slowly sinks while her eggs disperse. Multiply this by thousands and you have a mating swarm.

As we watched, others keyed on the worms, and within an hour, half a dozen small, hungry, cockeyed flounders appeared. As the number of flounders increased the number of worms decreased. Then, a two-foot long striped bass arrived, ate a few worms and picked-off a few flounders. By the time the yacht’s TV broadcast the 11 o’clock news all that remained on the surface were a few scraps of flounder and a forlorn worm or two.

Who would have guessed such a mating frenzy could be found only inches from the stern of a Newport yacht? I wonder how David Attenborough would have handled this true-life adventure?