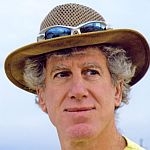

(HOST) As winter weather approaches, naturalist and commentator Ted Levin has been checking up on some late summer babies.

(HOST) As winter weather approaches, naturalist and commentator Ted Levin has been checking up on some late summer babies.

(LEVIN) A recent cold snap got me thinking about timber rattlesnakes, whose place in the pantheon of Vermont wildlife is precarious at best. Rattlesnakes are sun-loving serpents with deep southern roots. That they survive at all in the Northeast is remarkable.

Timber rattlesnakes dwell on our state’s western edge, where the Taconic Mountains fade into the Southern Lake Champlain Valley; it’s the northeastern fringe of their range, which extends from central Florida northward to Vermont and the foothills of the Adirondacks. On their western front, they range from east Texas northward to southeastern Minnesota. In between, timber rattlesnakes are found here and there throughout the deciduous forest biome, denizens of swamp or ledge depending on where in their vast range you’re looking.

Rattlesnakes are susceptible to cold. Cold weather numbs them; cold weather kills them, particularly inexperienced snakelets that follow invisible scent-trails laid across the woodland floor by older snakes that have passed that way before, perhaps a few dozen times. In autumn, reaching the security of a den (there are only three in Vermont) is a matter of life or death.

In late August, I had visited two rattlesnake-birthing sites, rock studded and nearly treeless, where pregnant females lay in the sun, too heavy to hunt, surviving off the proceeds of bygone summers. Half a dozen snakes stretched on warm slabs or coiled beneath rock awnings, with six to twelve oval embryos ripening inside each of them like peas in ophidian pods.

By September 14th, the mother snakes had given birth. They looked deflated with their loose skin draped over racks of ribs. A total of forty-five snakelets coiled at their mothers’ sides. The cold snap got me thinking about the fate of those newborns.

In Vermont, female rattlesnakes reach breeding-age by their ninth year (males somewhat earlier) and breed every three to five years thereafter.

Survival is a precise calibration between climate and topography, tempered by the snake’s own behavior. Heat-seeking snakes caught away from the den in cold weather temporarily coil under leaves or shelter in rock crevices. Snakelets are more susceptible to cold than adults; their metabolism winds down to tick… tick…

So on November 9th, I returned to where I’d seen them. It was 65 degrees and windy. I didn’t expect to see any rattlesnakes so late in the season, but I looked anyway. The sky was gauzy white. The rocks cool.

And there were two of them; a foot long, thumb-thick, and the color of rock. They were basking with a garter snake in a communal sunbeam. Far from their mother’s den, they may be forced by November weather to join the garter snake for the winter if they don’t get motivated soon.