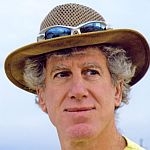

(HOST) Commentator Ted Levin has been thinking about horses – and prehistoric America.

(HOST) Commentator Ted Levin has been thinking about horses – and prehistoric America.

(LEVIN) On a recent summer morning, I took my wife’s thoroughbred, Hellacious, for a walk along our dirt road. A gelding 17 hands high, Hellacious is tan with a white facial blaze. He moves with swift and powerful precision, but still shies away from wind blown leaves and flapping jackets.

As we walked, Hellacious took every opportunity to browse the leaves and twigs of beech along the side the road. He had no interest in black cherry or red oak, nor in sugar maple or ash – both of which I offered; both of which were rejected. Except for the deep-green shade they provide, hemlock and white pine were also ignored.

There is a vague, but interesting connection between beech trees and horses – and perhaps I’m making too much of this – but both evolved in the New World tropics.

Beech spread north from the jungles of South America into the temperate woodlands of North America; and undoubtedly met horses in the well-watered woodlands on the eastern half of the continent. Was it just coincidence that Hellacious preferred beech leaves to other hardwoods or did the horse recognize a prehistoric food source, one his ancestors might have browsed millions of years ago? Whatever the reason, my latent interest in horse-evolution was rekindled by this experience.

Modern horses, wrote the late Harvard paleontologist Stephan Jay Gould, "represent the limit of evolutionary trends for the reduction of toes," which is to say that if horses had evolved to lose their single supportive toe they wouldn’t have a leg to stand on – quite literally.

The ancestor of modern horses first appears in the fossil record 45 million years ago in North America when the entire continent was a hot, steamy jungle. By the late Miocene Epoch, ten million years ago, twelve different kinds of horses roamed the North American grasslands. Some had stripes, all were three-toed, and were either browsers or grazers. One apparently underwent seasonal mass migrations across the continent much like African zebras do today.

Horses and their surviving relatives, rhinoceros and tapir, are the sole surviving members of the ancient mammalian order Perissodactyla, the odd-toed ungulates. Eventually, they were out-competed and overwhelmed (from an evolutionary standpoint) by a more modern order of mammals… the Artiodactyls, or even-toed ungulates; these include among others, deer, sheep, goats, antelopes, cows, camels, pigs, hippos, and pronghorns, which are not true antelopes but an endemic North American family.

The last wild horse disappeared from North America 13,000 years ago, likely with an Ice Age spear point embedded in its ribs. Columbus brought horses from Europe to the Bahamas in 1493, where, ironically, they had never lived before. In 1519, horses reached Mexico with Hernando Cortez. There they escaped, flourished, and spread northward, reclaiming much of the western half of the continent. By the middle of the 19th century wild mustangs were nearly as numerous on the Great Plains as bison, numbering more than two million.

Watching Hellacious nibble beech leaves is like watching the ocean roll. It’s rhythmic, peaceful, and steeped in deep history.