(Host) VPR’s John Dillon spent time in northern Quebec this month touring the area where Hydro-Quebec is completing construction of a five billion dollar river diversion project.

The work is part of the provincial utility’s effort to position itself as supplier of clean, renewable energy to the U.S. market.

But native Cree in the region question the "green label." They say the diversion of major rivers, and the construction of dams and dikes has dramatically changed the ecology in a region where their ancestors have hunted, fished and lived for generations.

In today’s report, John Dillon explores how the development of "big hydro" is playing out along the Rupert River.

Visit the main Big Hydro web page

(Sounds of a roaring river)

(Dillon) Head north about 600 miles from the Canadian border. Then turn east on a gravel road called the Rue du Nord. Drive another few hours and eventually you’ll come here to where the water roars – a spot where a mountain has been dismantled and where the Rupert River is blocked by a massive rock dam, about 1,400 feet long.

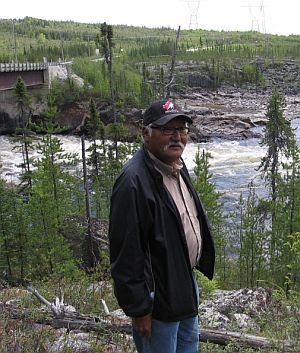

Steel gates anchored to bedrock are capable of removing three-quarters of the water from the river’s natural path so it can be used to generate electricity hundreds of miles away. Lawrence Jimikin is the Cree liaison with Hydro-Quebec from the nearby village of Nemaska. Despite his relationship with the utility, Jimikin has mixed feelings about the project. He lights a cigarette and looks down at the tremendous rush of white water.

Steel gates anchored to bedrock are capable of removing three-quarters of the water from the river’s natural path so it can be used to generate electricity hundreds of miles away. Lawrence Jimikin is the Cree liaison with Hydro-Quebec from the nearby village of Nemaska. Despite his relationship with the utility, Jimikin has mixed feelings about the project. He lights a cigarette and looks down at the tremendous rush of white water.

(Jimiken) "Right now the flow there is at 416 cubic meters per second. At the end of June, it will be 127, about 25% of what is actually coming through there now. It’s impressive, but depressing."

(Dillon) The Rupert diversion dam would be impressive by itself. But it’s actually just one piece of a construction project that funnels water from the Rupert and two other rivers to power generating stations, almost 200 miles north.

(Jimikin) "So there’s three river basins that are affected by all this. You’ve got the Rupert, the Lemare, and Nemaska River. And all the water eventually goes into the existing EM reservoir."

(Dillon) This is an engineering project that has re-shaped the earth. Hydro-Quebec built a series of four dams, 74 dikes and bored a tunnel more than a mile through a mountain to send 70% of the Rupert’s flow north. The water is used to boost existing reservoirs and eventually powers four separate generating stations before reaching reaches James Bay.

The result is an additional 918 megawatts of electricity, roughly equivalent to Vermont’s entire electricity demand.

Taking that much water out of a river is bound to have an impact. Jimikin says the utility maintains a higher flow in the spring to protect fish habitat and spawning areas. He says in a few weeks, the steel doors will close and the river level will drop.

(Jimikin) "They are on steel cables. Doors are raised up and down by steel cables. And it’s electronic; they’re controlled by Montreal, from a system in Montreal."

(Dillon) The steel gates were closed for the first time last November. And some of the Cree, who have used the Rupert for centuries, say they have already seen the impact.

(Dillon) The steel gates were closed for the first time last November. And some of the Cree, who have used the Rupert for centuries, say they have already seen the impact.

(Orr) "After they dammed it, after they closed the gates, the water went down dramatically. It was from a pristine river down to a river that hardly even trickled any more."

(Dillon) Roger Orr also lives in the village of Nemaska. He works as a drug and alcohol counselor, and he hunts and fishes throughout the region. Orr says the fluctuating river levels make the ice dangerous to cross in the winter. And he worries about the sturgeon and other fish that need free-flowing water to spawn.

(Orr) "All the places where the fish were and all the places where the water flowed, even the beaver lodges, they were just right out of the water."

(Dillon) Hydro-Quebec says it has protected the ecosystem by maintaining adequate flow in the rivers to support fisheries. New spawning areas have been built for sturgeon. And the company has commissioned several studies of fish populations.

Quebec Premier Jean Charest talked up the environmental benefits as he made the pitch for the provincially owned utility at a meeting last winter of the national Governors Association.

(Charest) "From Quebec‘s point of view we sell clean, renewable hydro electricity to our neighbors. We sell some to our neighbors in Canada. There should be a recognition in American legislation that large-scale hydro should be a renewable energy. It is a renewable energy."

(Dillon) Cree liaison Lawrence Jimikin says sturgeon and other fish are still in the Rupert and other rivers despite the dams.

(Jimikin) "They’ve tried to develop new spawning grounds for sturgeon. We don’t know how successful they are yet. There are sturgeon spawning, yes. But unfortunately to what degree is still yet to be determined."

(Dillon) Hydro-Quebec is also monitoring mercury levels in fish. The toxic metal leaches from soil that’s been flooded and is particularly dangerous for babies and pregnant women. A report on the research says that of 123 women tested, 3% had elevated mercury levels, although still below the safety threshold.

Before it was channeled north, the Rupert flowed from Lake Mistassini about 200 miles west to James Bay. The river was an ancient travel route for the Cree, and natives still use the river for transportation.

Robert Matoush is a Cree guide who helped lead one of the last trips down the Rupert while it was still a free flowing stream. He remembers when most Cree lived nomadically, following their trap lines in the winter.

Robert Matoush is a Cree guide who helped lead one of the last trips down the Rupert while it was still a free flowing stream. He remembers when most Cree lived nomadically, following their trap lines in the winter.

(Matoush) "In the old days we were living in tents a long time ago." (big laugh). Dillon: "And what did you eat in the winter?" Matoush: "Like rabbit, partridge, beaver, moose, bear."

(Dillon) When Matoush laughs the creases in his face almost obscure his eyes. But the smile fades as he talks about the Rupert today.

(Matoush) "Well, it’s kind of too dry for canoeing, eh? We won’t be able to canoe anymore. I think they’re going to just have water when they open the gates. That’s going to be the only time you’ll have a chance to paddle. But it’s going to be hard for the people. I guess it will be gone forever."

(Dillon) For VPR News, I’m John Dillon

Visit the Series Homepage