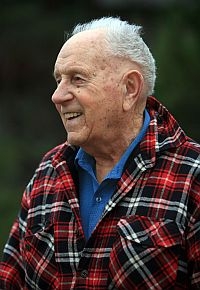

(Host) One of the pioneers of modern wilderness conservation in the Northeast passed away recently. Clarence Petty was 104 years old.

(Host) One of the pioneers of modern wilderness conservation in the Northeast passed away recently. Clarence Petty was 104 years old.

He helped to protect vast forests and lakes in New York’s Adirondack and Catskill Mountains. The wild areas he fought to defend are the largest in the East, far bigger than the White Mountains National Forest in New Hampshire or Baxter State Park in Maine.

As part of a collaboration with Northeast public radio stations, North Country Public Radio’s Brian Mann has this remembrance.

(Mann) When Clarence Petty was born in 1905, his father was dirt poor, a squatter living in a cabin on state land in New York’s Adirondack Mountains. He was interviewed for a profile seven years ago.

(Petty) "My father was a guide. He had a place fixed up for himself and that’s where we lived back in the woods. At that time, almost everybody lived in the woods in the Adirondacks — that was everything what we had."

(Mann) Petty grew up trapping and hunting. That early education stayed with him as the country began to develop rapidly as rivers were dammed and as suburbs gobbled up forests.

(Petty) "Mother shook her fingers at us. She said you got to go down to Saranac and get a high school education at least. So in winter we strapped on the snowshoes."

(Mann) And he and his brothers trudged 16 miles to school every week – and home again on weekends.

Those treks by snowshoe were the first steps in a journey deep into the spirit and politics of wild lands conservation.

In the late 1950s, Petty led a team for New York state that canoed and hiked some of the most rugged terrain in the East.

Dave Gibson, head of a group called Protect the Adirondacks, says Petty helped decide which forests would be preserved in a primitive state. That means no roads, no human structures, no motorized access.

(Gibson) "He began under the auspices of the Conservation Department to do the first wilderness studies. Where should these areas be and how should the lines be drawn on the map?"

(Mann) The project was revolutionary. It was half a decade before the Wilderness Act reinvented open space protection on federal lands.

(Mann) The project was revolutionary. It was half a decade before the Wilderness Act reinvented open space protection on federal lands.

Today the Adirondacks are the largest park in the lower-48, with more than 3 million protected acres.

It’s half a day’s drive from 70 million people, but it contains the kind of remote boreal forests and wild rivers that most people associate with Alaska or Canada.

On a wintry December day, trekking on Cascade Mountain near Lake Placid, I could see Petty’s legacy.

(Mann) "Mountains as far as the eye can see, cloaked in mist. In some places there’s just this incredibly pure crown of snow giving way to the dark green of the forest."

(Mann) In the East, fights over places like this have often meant locals who are pro-development squaring off against "green" outsiders.

But Clarence Petty was born and raised in these mountains. He was at ease with loggers and sportsmen.

Dick Beamish, with the Adirondack Explorer magazine, says that gave him a unique voice.

(Beamish) "He has tremendous credibility. He’s not an outsider saying, ‘Oh isn’t this nice, this playground we have in northern New York state, let’s keep it that way for us to enjoy. Clarence is an Adirondacker."

(Mann) That means deep roots and a family history that went back generations.

But to the end of his life Petty argued that there are plenty of places in the country for people, especially in the heavily urbanized Northeast.

A few special places, he insisted, should be carved out and protected and kept wild forever.

For VPR News, I’m Brian Mann.