(Mitch Wertlieb) The poetry of Robert Frost is deeply rooted in the rocky soil of Northern New England. Good Morning. I’m Mitch Werlieb.

(Mitch Wertlieb) The poetry of Robert Frost is deeply rooted in the rocky soil of Northern New England. Good Morning. I’m Mitch Werlieb.

Frost lived much of his life here – in Vermont, New Hampshire and northern Massachusetts. In fact, one of his books of poetry is titled North of Boston. And just as his poetry is full of references to the region, so too is the region full of reminders of his life here.

So it seems especially fitting that the choice of book for this year’s Vermont Reads program, sponsored by the Vermont Humanities Council, is about the life and work of Robert Frost. The book is called A Restless Spirit – The Story of Robert Frost by author Natalie Bober. We’ll be exploring Frost’s life and work all this week.

(Wertlieb) Natalie Bober, thank you very much for coming in and speaking with us about Robert Frost today.

(Bober) Well I thank you in turn for inviting me. It’s been a joy. Robert Frost has always been a joy to work with.

(Wertlieb) Amazing to hear you describe him that way – we think of Frost, I think, as a very hard, stubborn, rather rough man for a poet.

(Bober) I don’t really think he was that hard. He knew what he had to do and he had the courage to insist that he be given the freedom to do what he wanted to do.

(Wertlieb) Well that anticipates a question I had actually about what you think might be the biggest misconception about Robert Frost that people still hold perhaps.

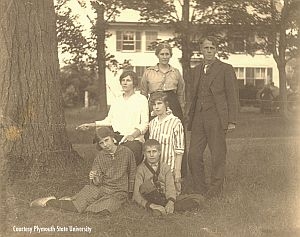

(Bober) Well, I think that they think that he was a harsh person and an unfeeling person. He wasn’t. He was a very warm and concerned family man. The love affair between Robert Frost and Elinor was just beautiful, but there was such a pull always. He wanted to earn money to support his family but he needed to write poetry and it was this pull always that was so difficult for him. And later in life when he was being invited to speak – "barding around" he called it – Elinor didn’t want him to do that. And he did it because he would earn money and they needed the money. She didn’t care and she wouldn’t go, even to listen to him speak. She waited at home for him but she wanted him to be hers. She wanted him just to write his poetry. Actually every poem he wrote, he said, can best be seen as a love poem to Elinor.

(Wertlieb) So much of his poetry seems to be concentrated on natural beauty – the natural world around us – and we think of all the beautiful poems written about the woodlands and as you say, snow falling, but to think that he had Elinor in mind through all of them.

(Bober) Through all of them, and he tried to teach his children to look at things the way he did. He thought that metaphor was extremely important – to explain one thing in terms of another – and you see that in so much of his poetry. But Leslie, his oldest daughter, described it years ago. She said they played a game and the children had to describe something and he sent them out to look at things and describe them… "and if we came back with something that looked as though it were only half a glance, he sent us back to look again." And she said, "Our papa was pretty good at this game, but we didn’t know he was a poet."

(Wertlieb) Bober wrote about Frost’s family life and his relationship with his wife Elinor in "A Restless Spirit".

(Bober) The children took turns riding beside "Papa" on the high, narrow seat of the horse-drawn hayrake. They rode beside "Mama" and held the reins of their horse, Eunice, when they went to do the Saturday grocery shopping in Derry Depot.

Sunday usually meant an all-day picnic across the orchard to the alders. Rob cleared the underbrush with an ax and clippers and Elinor would sit on a board bench that Rob had nailed between two young pine trees. She would mend stockings or read aloud to the children, and they in turn, would build dams, play house, using plantain leaves as their dishes, or hunt for mayflowers.

Those days – precious to all of them – were the days when Rob’s poetry was growing inside him. Robert Frost was almost the perfect example of William Wordsworth’s philosophy that poetry "takes its origin from emotion recollected in tranquility." Frost’s memories of this life on the Derry farm were later to be transformed into some of his most beautiful poems.

In the evenings, after Elinor and the children were all asleep, Rob continued to scratch out his poems by lamplight. When he wrote "The Pasture," a poem that urges "I shan’t be gone long.- You come too" he told Lesley he had written it for her, because she was the one who loved to trail after him on the farm. When she grew older, he confessed that he had actually written it for Elinor. Then, when Lesley had daughters of her own, he told them he had written it for them. Whatever "The Pasture" may have meant to the children, it is, unmistakably, a love poem to Elinor.

I’m going out to clean the pasture spring;

I’ll only stop to rake the leaves away

(And wait to watch the water clear, I may):

I shan’t be gone long. – You come too.

I’m going out to fetch the little calf

That’s standing by the mother. It’s so young

It totters when she licks it with hier tongue.

I shan’t be gone long. – You come too.

(Wertlieb) One of the people visiting the state for the Vermont Reads project is Robert Frost’s granddaughter, Robin Fraser Hudnut. Robin’s mother was Frost’s daughter Marjorie, who died not long after Robin was born. She spent a good deal of her childhood in an old stone farmhouse in Shaftsbury, cared for by her aunt and uncle – and by her grandparents, who lived in another house just a mile or so away. The Shaftsbury house – now the Robert Frost Stone House Museum – is full of memories for Robin Hudnut.

(Hudnut) I’m at the Stone House today because I have an opportunity to come and see the amazing achievement – by Carole Thompson really – who decided that the Stone House should become a Frost museum. And my daughter – Frost’s granddaughter – and my granddaughter – Frost’s great-granddaughter – are here with me as well as one of my daughters-in-law so we’re enchanted with all our memories and – oh I know what I could tell you is that there was a dog at this house. [Oh.] A husky. As I looked at the lawn I was remembering that Nanook, you know, would play with me on this lawn. [Whose dog was it?] And it was grandfather’s dog. [Oh okay.] Sort of a family dog [Umhum.] but he was my best friend when I was here. So I have many memories but not enough because I lived here when I was so little that I don’t remember enough but as you heard, with Isabella my memory’s come back! Yes. I love that poems can follow you from the youngest years to your oldest years. I have lots of favorites. My favorite today is “You Come Too”. Want to say it with me? (Recites with granddaughter Isabella – from memory – a variation of “The Pasture”. Comments in [brackets] above are Isabella.)

(Wertlieb) And we hope "you’ll come too", as we explore the book, the poetry and the life of Robert Frost all this week on VPR.

Tomorrow we’ll hear about Frost’s poetic imagery, and you can find more about Vermont Reads, this series and offer your own thoughts on our website VPR-dot-net.

Photo: George H. Browne Robert Frost Collection, Michael J. Spinelli, Jr. Center for University Archives and Special Collections, Herbert H. Lamson Library and Learning Commons, Plymouth State University