Visit the Series Homepage

Vermont Reads 2011: "To Kill A Mockingbird"

(Wertlieb) Good morning, I’m Mitch Wertlieb. Each year VPR collaborates with the Vermont Humanities Council’s statewide reading program, Vermont Reads. This year the Humanities Council has chosen a classic, "To Kill A Mockingbird" by Harper Lee. The book deals frankly with the issue of race, and we’ll take the opportunity this week to explore the state of race relations in Vermont.

(Wertlieb) Good morning, I’m Mitch Wertlieb. Each year VPR collaborates with the Vermont Humanities Council’s statewide reading program, Vermont Reads. This year the Humanities Council has chosen a classic, "To Kill A Mockingbird" by Harper Lee. The book deals frankly with the issue of race, and we’ll take the opportunity this week to explore the state of race relations in Vermont.

The novel, set in the South, chronicles the way a small town in the south is torn apart when a black man is accused of raping a white woman. In this scene, the narrator, Scout, recalls a conversation her father has with her brother, Jem. Through Scout, Atticus Finch explains why a previously friendly neighbor had threatened him:

(Excerpt) "Mr. Cunningham’s basically a good man," he said, "he just has his blind spots along with the rest of us."

Jem spoke. "Don’t call that a blind spot. He’da killed you last night when he first went there."

"He might have hurt me a little," Atticus conceded, "but son, you’ll understand folks a little better when you’re older. A mob’s always made up of people, no matter what. Mr. Cunningham was part of a mob last night, but he was still a man. Every mob in every little Southern town is always made up of people you know – doesn’t say much for them, does it?"

"I’ll say not," said Jem.

"So it took an eight-year-old child to bring ’em to their senses, didn’t it?" said Atticus. "That proves something – that a gang of wild animals can be stopped, simply because they’re still human. Hmp, maybe we need a police force of children . . . you children last night made Walter Cunningham stand in my shoes for a minute. That was enough."

(Wertlieb) 21st century Vermont can feel like a world way from a racially divided south.

Here Vermonters pride themselves on being tolerant of differences, more interested in a person’s character than in status, race, or personal beliefs.

But every so often something in the news puts that claim of tolerance in doubt. In Hartford, a black businessman is mistaken for a burglar and dragged in handcuffs from his own home.

An Arlington parent is cited into court for losing his temper at some kids allegedly taunting his adopted African-American daughter.

And as VPR’s Susan Keese explains, a visit to a barber shop raises questions.

(Aldrich) ‘Trim your eye brows a little bit? "(Customer) " If you would please…".

(Keese) For years Aldrich and his card-playing "regulars" have kept tabs on Main Street from Mike’s storefront window.

But an encounter last fall turned the spotlight the other way.

(Aldrich) "I was playing cards here at the table where we’re sitting. The fellow was coming up the stairs, he was well-dressed and what not- a black man. So he opened the door and asks if the barber’s in. I said, ‘No the barber’s not in, I’m sorry.’ That was my mistake."

(Keese) Aldrich says the man left.

(Aldrich) "But then, later while I was cuttin’ hair, I saw him walk by and look in."

(Keese) Aldrich wishes now he’d told the man that he didn’t know how to cut "black" hair. He says he’s tried but the results have been embarrassing.

Soon after, a letter appeared in the local paper from the would-be customer, an out-of-state physician who was thinking about moving to Vermont.

The doctor said his experience with the barber convinced him that Bellows Falls wasn’t a place where he’d want to set up a practice.

The story sparked national press coverage – and an anti-racism protest in the Bellows Falls Square.

Aldrich watched the protest from his shop, bristling at his neighbors’ accusations of prejudice.

(Aldrich) "You don’t even see black people. How can it be prejudiced? Months, a week you might see a black person in town."

(Keese) Curtiss Reed is a black Vermonter and the director of the Vermont Partnership for Fairness and Diversity.

Reed sees incidents like these as ‘teachable moments’ -opportunities for growth, as a once-monochromatic culture changes into a diverse one.

(Reed)"And what we hope as those incidences take place, that people take pause and re examine, what their assumptions are and what they have inherited out of no fault of their own in terms of attitudes and behaviors."

(Keese) Thirty-nine year old Curtis Green, who is also African-American, is a parts specialist for a local auto dealer. He hopes the doctor will see beyond his bad first impression.

(Keese) Thirty-nine year old Curtis Green, who is also African-American, is a parts specialist for a local auto dealer. He hopes the doctor will see beyond his bad first impression.

(Green) "That barber doesn’t represent Bellows Falls Vermont. What represents Bellows Falls Vermont are the people who protested afterwards, who were upset at his actions."

(Keese) Green first came to the area from Brooklyn as a 10-year-old Fresh Air kid.

He’s stayed close to the families and friends he met during his summers in the area which is one reason he moved to Bellows Falls permanently after college.

(Green) "It’s a white-dominated area but they’ll open their arms to anybody if you give them a chance."

(Keese) Not that he hasn’t had some bad experiences -But Green says they’ve are small compared to the good things.

Among his own and younger generations, Green says television and music – especially hip hop –have bred an understanding and eagerness to know people of color.

Green is glad to be raising his children here.

(Green) "I am more at ease being up here with my kids than I think I would ever be in Brooklyn. Besides the safety factor, it’s a beautiful place. Whether you hike Fall Mountain or go fishing…

(Keese) He says he likes the fact that people know each other here, that his children have had the same friends since kindergarten – a rainbow of faces, that Green sees as a good thing.

For VPR News, I’m Susan Keese.

(Wertlieb) Incidents like the one in Bellows Falls aren’t all that new. One event in the 1960s put Vermont’s racial tensions in the national spotlight. Commentator Tom Slayton has the story:

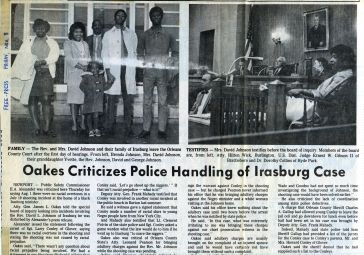

(Slayton) The tangled sequence of events that came to be known as "The Irasburg Affair" began July 19, 1968, with a racial attack on the home of a black Baptist minister named David Lee Johnson who had recently moved to Irasburg. Shots were fired at his home late at night from a speeding car.

(Slayton) The tangled sequence of events that came to be known as "The Irasburg Affair" began July 19, 1968, with a racial attack on the home of a black Baptist minister named David Lee Johnson who had recently moved to Irasburg. Shots were fired at his home late at night from a speeding car.

No one was injured, but the event had strong echoes of southern racist vigilante activities, and alerted Vermont to a distressing truth, one we had tried to ignore: racism – race hatred, actually – existed in our state.

Just how deep those despicable feelings ran and where they would be found would shock all of Vermont before the Irasburg Affair ended.

Immediately after the shooting, the Vermont State Police were assigned to guard Rev. Johnson’s home. But it became apparent that the police had become more interested in investigating David Johnson than in protecting him. They abruptly arrested him and a white woman who had been staying at the house on charges of adultery. A state police trooper said he had witnessed the two engaging in sex.

That shifted the focus of the case from the initial crime – the drive-by shooting at Johnson’s home – to Johnson’s own character and behavior. And it looked suspiciously as though the state police had moved slowly on the shooting case and pretty quickly on the adultery charges.

Suddenly, Vermont was in the national limelight – in a way that no Vermonter had ever wanted the state to be. Was clean little, green little Vermont a hotbed of racial hatred – up to and including those who should be enforcing the law? The national press corps descended upon Orleans County, and a formal Board of Inquiry was appointed by Gov. Philip H. Hoff.

Eventually Larry Conley of Glover was charged with breach of the peace in connection with the shooting. He pled no contest. The adultery charges against Johnson were dropped after the woman involved left the state and refused to return. She pleaded no contest and paid a fine, even though Johnson’s wife testified that no adultery had taken place because Johnson had been with her at the time of the alleged incident. And, given the turmoil surrounding them, it wasn’t surprising when the Johnson family subsequently moved away from Vermont.

It was a sad and inconclusive ending to a sad chapter in Vermont’s history.

The Irasburg affair proved, once again, that despite Vermont’s reputation for friendly acceptance, despite the state’s much-vaunted heroic participation in the Civil War, there is a dark side to our rural life. It was expressed in the last century by the sudden flourishing of the Ku Klux Klan here, and it is expressed now in racial incidents directed against blacks, Muslims, gays – anyone, really, whom the hate-mongers decide is different and somehow threatening.

The Irasburg Affair, and other instances of Vermont’s own home-grown brand of intolerance are worth remembering, if only to remind ourselves that evil can grow anywhere it is allowed to grow – and it must be opposed, even here, in our own the quiet hills and villages.

(Wertlieb) Tom Slayton is editor emeritus of Vermont Life.

Our series, Vermont Reads, To Kill a Mockingbird continues all this week. Tomorrow we’ll take a look at changing definitions of race.

For VPR News, I’m Mitch Wertlieb.