(Mitch Wertlieb) Japanese attacks on Pearl Harbor meant a world at war for most Americans in 1941. But for Japanese-Americans, it also meant a world upended, a world that would never be the same for them or their families.

(Mitch Wertlieb) Japanese attacks on Pearl Harbor meant a world at war for most Americans in 1941. But for Japanese-Americans, it also meant a world upended, a world that would never be the same for them or their families.

I’m Mitch Wertlieb.

We return this morning to Vermont Reads, the statewide reading program sponsored by the Vermont Humanities Council. This year’s book is "When the Emperor Was Divine," a fictional account by Julie Otsuka of one family’s life before, during and after their internment during the war.

For the 120-thousand people who were sent to "relocation camps," the experience was anything but fiction, as this old newsreel illustrates.

(Tape from newsreel)

According to Dorothy Whitney Yamashita, a native Vermonter now living in Lebanon, New Hampshire, ripples from the internment were felt throughout the country, even in small town New England. And they still are.

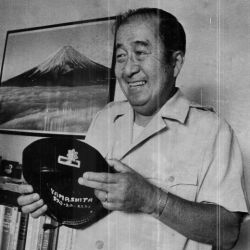

(Yamashita) "My husband’s legal name is Kanshi Stanley Yamashita, which means YAMA means ‘mountain’ and SHITA is ‘underneath’. So Yamashita is ‘underneath the mountain.’"

(Yamashita) "My husband’s legal name is Kanshi Stanley Yamashita, which means YAMA means ‘mountain’ and SHITA is ‘underneath’. So Yamashita is ‘underneath the mountain.’"

(Wertlieb) Stan Yamashita died in 2005, but the memories of his life immediately after the war started… live on through Dorothy.

(Yamashita) "I met him in ethics class at Antioch College. Anyone who served in the U.S. military in World War II, was eligible to apply for tuition for the college of their choice. He was a Japanese-American. And when World War II broke out on December 7th, he and his family lived in Terminal Island, a fishing village near Long Beach, California. And they were all in church on Sunday morning. And they were all saying "the Japs bombed Pearl Harbor. Where’s Pearl Harbor? Never heard of that." But they did know that they were of Japanese descent. And from the beginning they knew that they were in trouble."

(Wertlieb) Fathers were arrested within a week or two and sent away. It wouldn’t be until late February of 1942 that there would be a "mass evacuation" of Terminal Island.

Stan Yamashita’s family was sent to Arizona. But he learned he could leave the camp if he were accepted to college.

(Yamashita) "So he applied to Bethel College, Minnesota. He studied there for one year and then heard about the military intelligence school nearby in Minnesota and volunteered for the army."

(Wertlieb) Stan Yamashita spent thirty years in the American military as an intelligence officer. At age 18, he interrogated Japanese prisoners of war in the Philippines. During the Korean conflict, he volunteered to return to active duty and served in counter-intelligence.

When Stan retired from the military, he and Dorothy returned to California, where they helped start the Japanese American National Museum in Los Angeles. Stan and his father were also among those who testified before Congress in the 1980s, describing how their lives – and so many others – had been completely disrupted by the internment.

(Yamashita) "Everything was gone, the whole of Terminal Island, the whole fishing village had been razed. There was nothing there, so anyone who had lived on Terminal Island had to start from scratch. In the case of my in-laws, we felt they were very fortunate to obtain work with a fairly wealthy American family. Grampa was the groundskeeper and Gramma was the cook."

(Wertlieb) Another Vermonter whose family was interned during the war is Tracy Tsugawa. Today she’s a member of the Vermont Human Rights Commission. Her parents’ families went to two separate camps.

(Tsugawa) "My father and his sisters and his parents went to Topaz in Utah, and my mother and her mother, who was thinking about going back to Japan, they ended up at Tully Lake, which was probably the worst of the camps during the war in the sense that that was where they sent the disloyals, the people that were most suspect from the government’s perspective, people who were considering repatriation back to Japan. And she was I believe nine at the time that they went into the camp."

(Tsugawa) "My father and his sisters and his parents went to Topaz in Utah, and my mother and her mother, who was thinking about going back to Japan, they ended up at Tully Lake, which was probably the worst of the camps during the war in the sense that that was where they sent the disloyals, the people that were most suspect from the government’s perspective, people who were considering repatriation back to Japan. And she was I believe nine at the time that they went into the camp."

(Wertlieb) "What’s your understanding of what life was like during the internment for these people?"

(Tsugawa) "Well, they were only allowed to take what they could carry. So people lost homes, they lost farms, they lost many, many family heirlooms, and… It’s basically two suitcases per person, I think, and I have a book of oral histories of Japanese-Americans who were in various camps throughout the country and one person was saying how her mother told them to put on as many clothes as they could in terms of layers… just so that they had more to take with them."

(Tape from newsreel)

(Wertlieb) Forced evacuation, whether sudden or with plenty of notice, whether due to a natural disaster or man-made, is painful and full of loss. This point is brought home in author Julie Otsuka’s book, "When the Emperor Was Divine," when the mother realizes that family pets must be left behind. Her husband is already interned in Texas. She and her children will be evacuated soon. She is dismantling their life. She gives the cat to a neighbor. She will set a pet bird free. But she knows that no one will take the old, infirm dog. And it can’t be left to fend for itself. Ostuka reads from her book.

(Otsuka) The woman sat down on a rock beneath the persimmon tree. White Dog lay at her feet and closed his eyes. "White Dog," she said, "look at me." White Dog raised his head. The woman was his mistress and he did whatever she asked. She put on her white silk gloves and took out a roll of twine. "Now just keep looking at me," she said. She tied White Dog to the tree. "You’ve been a good dog," she said. "You’ve been a good white dog."

(Otsuka) The woman sat down on a rock beneath the persimmon tree. White Dog lay at her feet and closed his eyes. "White Dog," she said, "look at me." White Dog raised his head. The woman was his mistress and he did whatever she asked. She put on her white silk gloves and took out a roll of twine. "Now just keep looking at me," she said. She tied White Dog to the tree. "You’ve been a good dog," she said. "You’ve been a good white dog."

Somewhere in the distance a telephone rang. White Dog barked. "Hush," she said. White Dog grew quiet. "Now rollover," she said. White Dog rolled over and looked up at her with his good eye. "Play dead," she said. White Dog turned his head to the side and closed his eyes. His paws went limp. The woman picked up the large shovel that was leaning against the trunk of the tree. She lifted it high in the air with both hands and brought the blade down swiftly on his head. White Dog’s body shuddered twice and his hind legs kicked out into the air, as though he were trying to run. Then he grew still. A trickle of blood seeped out from the corner of his mouth. She untied him from the tree and let out a deep breath. The shovel had been the right choice. Better, she thought, than a hammer.

Beneath the tree she began to dig a hole where the soil was on top but soft and loamy beneath the surface. It gave way easily. She plunged the shovel into the earth again and again until the hole was deep. She picked up White Dog and dropped him into the hole. His body was not heavy. It hit the earth with a quiet thud. She pulled off her gloves and looked at them. They were no longer white.

(Wertlieb) Author Julie Otsuka, reading from her book, When the Emperor Was Divine, the story of a family caught up in the internment of Japanese Americans during World War II.

Tomorrow we’ll hear about the journey from home to camp, from the known to the unknown, mostly by train.

For VPR News, I’m Mitch Wertlieb.

Explore the entire series:

Visit the Vermont Reads 2009 Homepage