Tropical Storm Irene may be the most dramatic example, but every year floods damage or destroy property in Vermont.

Tropical Storm Irene may be the most dramatic example, but every year floods damage or destroy property in Vermont.

Despite that, there continues to be construction on floodplains.

Recently, though, the state has adopted a new approach. It’s urging towns to adopt new bylaws that would prohibit development in many areas likely to flood.

For decades communities have relied on FEMA maps as a guide to flood prone areas. The maps are the basis for the National Flood Insurance Program, which offers property insurance to owners whose buildings might flood.

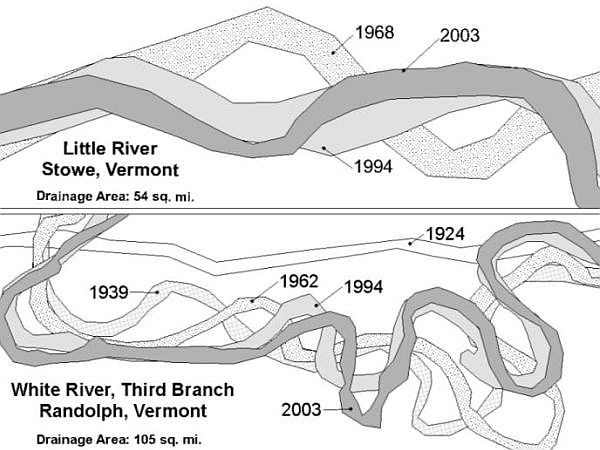

But state officials say the FEMA maps are just snapshots of a river at a particular moment. They don’t really give us an accurate picture because they don’t take into account the fact that Vermont rivers and streams are constantly moving around.

Because of geography and human activity, when a Vermont river floods, it causes erosion outside the streambed that alters the landscape and changes where the water flows.

State officials are now working with towns to create maps that take that into account and give a clearer picture of the area over which a river moves as it changes over time. The name they’ve given to this area is the "fluvial erosion hazard area."

Tom Jackman is the planning director in Stowe, which has adopted zoning bylaws that recognize and protect the area beyond the banks of the West Branch River where it might need to spread as it carries runoff from Mount Mansfield.

"Basically it’s a corridor that’s about 300 feet wide that the river flows through," he explains.

"It’s that area that the river naturally wants to move around in over time. By adopting the regulations what we essentially said was that no new structures are going to get built within this corridor."

What Stowe has done by adopting Fluvial Erosion Hazard bylaws is a departure from years of accepted practice.

"It’s a completely different scientific approach," says Rob Evans, is river corridor and floodplain manager with the Agency Of Natural Resources.

"We’re not saying how deep or how high the floodwaters are going to get. That’s what FEMA’s process does. We’re saying, ‘How much room does a river need over time.’"

It’s also a different approach to how these areas should be protected. For decades most towns have followed the FEMA model, which allows development of much of the floodplain – as long as the buildings meet certain standards.

Now Vermont is taking an avoidance approach to keep development out of erosion hazard areas.

For the past five years, the Vermont Agency of Natural Resources has been urging towns to adopt erosion hazard bylaws to protect the larger floodplain.

Evans says there’s little that can be done about the development that’s already in these areas. But where they’re undeveloped, it’s important to keep them that way, adding, "That’s kind of the starting point whenever I’m talking to individuals or communities or town boards: Can we all agree that we don’t want to make things worse. If we can start there, then we can work the kinks out in terms of what the right balance is for that community. What works for one community may not be right for the other community."

So far at least 42 towns have some form of erosion hazard protection. Evans says he tries to make the case that communities that protect a river’s erosion hazard area will be less vulnerable to the human and financial costs of future floods.

But in many cases the erosion hazard areas are more extensive than FEMA’s mapped floodplain. Evans says a number of towns have decided not to adopt bylaws because they would limit or prohibit a landowners’ ability to develop.

"Land use regulation is difficult," Evans says. "For a community to sign on to this is really a big deal. You’re really making a decision, a regulatory decision to say, we’re going to limit the use of your land."

Evans says the state hopes to develop more incentives to encourage towns to adopt the bylaws.