(Host) The explosion last month at the Kleen Energy power plant site in Middletown, Connecticut, tore apart a billion dollar construction project and killed six men.

Local and state police and fire departments, OSHA and the ATF converged on the site to investigate.

But one federal agency showed up that many had never heard of: the U.S. Chemical Safety Board.

The CSB is charged, under the federal Clean Air Act, with investigating the cause of major chemical accidents.

But the Safety Board doesn’t always get the access it says it needs to do its job. As part of a collaboration with Northeast public radio stations, Nancy Cohen of WNPR in Hartford reports.

(Cohen) Earlier this winter workers were close to finishing the construction of one of the biggest gas-fired power plant projects in the Northeast. On the morning of February 7th they were doing what’s considered a common procedure when installing new gas pipe: blowing natural gas at high pressure through the pipe to clean it. Mike Rosario, the business agent of the local Pipefitters union, was at his home close to the site, that Sunday.

(Rosario) "I heard a loud bang. I looked out window and I saw a big cloud of smoke and I knew that something seriously went wrong."

(Cohen) And it had. Six men would lose their lives. 26 were injured.

The next morning investigators from the U.S. Chemical Safety Board arrived in Middletown from Washington, D.C. They drove up the road to the explosion site. But they didn’t get very far. CSB Spokesmen Daniel Horowitz said Middletown police turned them away.

(Horowitz) "Where I and really our investigative team would like to be is at the scene of the explosion, documenting the site, tagging evidence, interviewing key witnesses and arranging for the proper scientific, objective testing of the evidence."

(Cohen) That’s what the Safety Board is supposed to do. When Congress established the Board in 1990 it wanted independent, scientific investigators looking into workplace accidents, rather than agencies, like the EPA, that regulate industry.

Much like the National Transportation Safety Board, which investigates plane accidents, the CSB’s mission is to figure out what went wrong and to recommend new safety measures. But not many people have heard of them. That was true in Middletown.

(Guiliano) "It’s my understanding they’re a civilian agency. They really don’t have a role in what’s going on there right now."

(Cohen) That’s the Mayor of Middletown, Connecticut, Sebastian Giuliano the day after the explosion, talking about the Chemical Safety Board.

(Guiliano) "And frankly they’d just be in the way. That’s what I’ve been told."

(Cohen) Middletown Acting Chief of Police Patrick McMahon explained the site was being treated as a crime scene, where evidence is preserved so it can be admissible in court.

(McMahon) "Until we know that criminal negligence was not responsible we treat it as if it was because once the evidence is gone, it’s gone."

(Cohen) Two days after the explosion C.S.B. investigators were allowed on site, but only around the perimeter. Spokesmen Daniel Horowitz.

(Horowitz) "They were backed away from areas of the plant that they wanted to examine in order to conduct the federal investigation and that is, well, it’s rather unbelievable."

(Cohen) But it isn’t the first time the Safety Board has been blocked from an explosion site.

(Farrell) "We had no knowledge of them. I had never heard of them."

That’s Kevin Farrell the Deputy Fire Chief from Danvers, Massachusetts, where a factory exploded in 2006.

(Farrell) "There were numerous, numerous agencies there. We had the ATF, DEP, the EPA, the state and local authorities. What made it difficult was there wasn’t one person on site that had even heard of the CSB until the time that they showed up at that explosion."

(Cohen) CSB investigators didn’t get access to the core area on the Danvers site for about a week. And only after they reached an agreement with state and local agencies. Farrell those kinds of agencies should get to know the CSB.

(Farrell) "They bring a lot to the table. They have chemical engineers. They have structural engineers. I think they could have a positive outcome on the investigation."

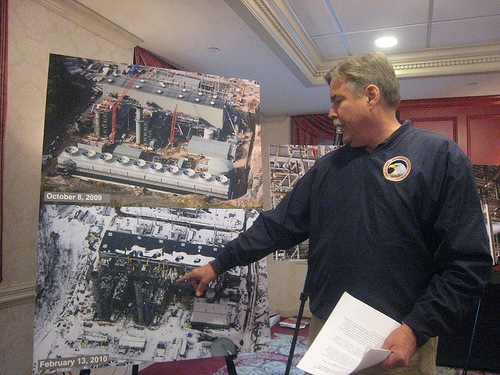

(Cohen) Back in Middletown, four days after the explosion, CSB investigators were finally allowed to interview all witnesses and examine the site, but not some of the key evidence. About two and a half weeks later CSB lead investigator Donald Holmstrom held a press conference to explain what he and his team had learned so far.

(Holmstrom) "Initial calculations by the CSB investigators reveal that approximately 400,000 standard cubic feet of gas were released in the atmosphere near the building in the final ten minutes before the blast. That is enough natural gas to fill the entire volume of a pro basketball arena from the floor to the ceiling."

(Coyen) At that press conference on February 25 Holmstrom said the CSB and OSHA were negotiating with state and local authorities for access to evidence.

(Holmstrom) "We’re very hopeful. There have been some positive signs and we’re encouraged that such an agreement will be reached."

(Cohen) But now, more than a month after the explosion there’s still no deal. The CSB wants to examine a gas detector that may have recorded details from the time of the explosion. Middletown police say they are still investigating the incident and declined to comment on the CSB’s access to evidence.

Quinnipiac University law professor Jeffrey Meyer, a former federal prosecutor, says police may be withholding evidence because they don’t want certain information to become public.

(Meyer) "It’s sometimes in the interest of the police to limit the information that’s publicly known so that potential witnesses out there cannot tailor their stories to fit what’s publicly known."

(Cohen) Meyer says it might also be a turf battle between local, state and federal agencies.

Glenn Corbett, who teaches fire investigation at the John Jay College of Criminal Justice in New York, says the CSB has expertise that could help local law enforcement with its investigation.

(Corbett) "Knowing exactly what happened or how this explosion occurred will dictate what kind of criminal charges are going to be filed. You know. Was it negligence? Was it intentional? I mean all these are all kinds of things that will come out of this technical investigation."

(Cohen) And Corbett says the technical investigation may have even a higher purpose than the criminal.

(Corbett) "Isn’t it even more important to not let this happen again and kill another, in this case six people? Isn’t that equally or perhaps even more important?"

(Cohen) While the police and safety investigators continue to negotiate, the families and the workers are grieving.

Chuck Appleby, who represents the Carpenters Union, Local 24, says he wants the Chemical Safety Board involved to come up with better safety procedures.

(Appleby) "Our hearts bleed for our brothers, those who are injured, the families. We owe it to them. We owe it to them to be involved in some shape or form with whoever it is that’s going to carry the water for us to make it safer going forward so they didn’t lose their lives in vain."

(Cohen) The Chemical Safety Board is now turning to Congress to strengthen the statute that defines its authority at disaster sites, like the one in Middletown.

For VPR News, I’m Nancy Cohen.

(Host) Northeast environmental coverage is part of NPR’s Local News Initiative. The reporting is made possible, in part, by a grant from United Technologies.