(Host) Dammed up rivers fueled the first industries in the Northeast. But they also wall off rivers and stop fish from migrating upstream.

In recent years more than 20 dams have been knocked down in the region. This month marks the ten-year anniversary of one of the first to come down: the Edwards Dam in Augusta, Maine.

As part of a collaboration with Northeast public radio stations, Susan Sharon reports there are tradeoffs to dam removal – especially in an era of climate change.

(Sharon) The Edwards dam on the Kennebec River stretched 920 feet long and 24 feet high. Not a huge dam, but big enough to stop fish. Groups like Trout Unlimited lobbied state and federal officials to get it removed. Fisherman Jim Thibodeau says they were skeptical about the idea.

(Thibodeau) "One legislator says: geez, look what we’re gonna lose? I says: Look what we’ve already lost!"

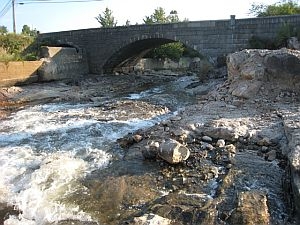

(Sharon) When the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission finally ordered the dam demolished, it marked a milestone. Never before had regulators determined that the benefits of removing a functioning hydroelectric dam outweighed the value of the electricity it produced. In July, 1999 the 172-year old Edwards Dam was breached and 17 miles of the Kennebec set free.

(Reardon) "I got one on! All right. I got one on.

(another voice in background) We got a double!"

(Sharon) Jeff Reardon of Trout Unlimited has just landed his first American shad. Until the dam came down shad were rarely seen this far up the Kennebec. Other fish have also returned.

(Reardon) "To me, the most remarkable thing is the spring run of alewife. Seeing a river that has two million fish it is just phenomenal. It’s like seeing wildebeast on the plains of Africa or bison on the American great plains. This is one of the great planetary migrations."

(Sharon) Blueback herring have also returned along with striped bass, some Atlantic salmon and an unusual, long, bony fish. From his boat, Willy Grenier spots one.

(Grenier) "Oh my God! You just missed a sturgeon. It was about a six-foot sturgeon. He just jumped out of the water right over there."

(Sharon) Not just fish, but birds that eat fish, are returning: eagles, osprey, herons, and on this day, a pair of loons. Dave Courtemanch of the Maine Department of Environmental Protection says things changed almost immediately after the dam came down. Water quality improved and insects that fish feed on also came back.

(Courtemanch) "We had like a 30-fold increase in the number of organisms that we were catching in sampling devices…caddisflies, stone flies, mayflies. They were there within two months. It was quite remarkable."

(Sharon) Courtemanch says the return of aquatic life reminds him of the phrase: "build it and they will come."

(Courtemanch) "If you return a habitat to pre-existing conditions, there are organisms that are adapted and they will find it rather rapidly."

(Sharon) While few can argue about the benefits of taking the dam down…today there would probably be a different spin on its removal because of climate change. Edwards dam only produced enough power for about one thousand homes. But given the interest in renewable energy, Fred Ayer of the low impact hydropower institute says today even a little carbon free energy goes a long way.

(Ayer) "I guess we might view it a little differently today where we’re thinking that all things count. I mean people are putting solar panels on the house and certainly that’s not gonna provide electricity for too many people, but it’s worth doing and I think this would have been the same way."

(Sharon) Ayer, who worked as a consultant for the owners of Edwards Dam, is now working on a project to restore the Penobscot River in northern Maine. On that river, agreements have been reached to make up for removing one dam by increasing hydro power on another part of the river. The idea is to reach a balance between green energy and damaged ecosystems.

For VPR News, I’m Susan Sharon.