(Host)

(Host)

All this week, VPR celebrates

Women’s History Month with Vermont Women In History, a series of essays on Vermont Women and the

Law. It coincides with the the Vermont Commission on Women’s publication

of the 6th edition of "The Legal Rights of Women in Vermont," a

handbook that explains laws governing issues like employment, domestic

relations, property, housing, government benefits, health, violence, and

immigration. Today many of these laws apply to women and men equally,

but writer, historian and commentator Marilyn Blackwell says that wasn’t

always the case.

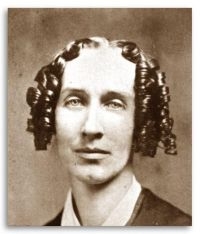

(Blackwell) Back in the 1840s reformer Clarina Howard Nichols argued that married women were legally dead.

She complained bitterly that she had no rights to her own clothing and

chided Vermont lawmakers for having "legislated our skirts into their

possession!"

Vermont’s

early laws were based on colonial beliefs about the different

capacities and social roles of men and women. The marriage system

followed the British common law doctrine of coverture, which obligated

husbands to protect and support their families, and in turn they

controlled personal and real property, household labor and wages, legal

contracts, custody of children, and inheritance. Wives held no

individual rights under the law until they became widows. Though single

women could inherit and own property, they needed a male trustee to

represent their legal interests.

By

the early nineteenth century, it became obvious to lawmakers that this

system had its drawbacks; it could leave a family in poverty and

dependent upon the town if a man failed to provide, if he deserted his

family, or if he died.

One of the earliest acts providing wives with individual rights allowed

prisoners’ wives to make legal contracts so they could support

themselves.

Poverty

Poverty

was the problem that drove Clarina Howard Nichols of Brattleboro to

advocate for married women’s property rights. Her first husband had

spent her inheritance, frustrated her attempts to make a living, and

threatened to take away her children; she had no way to support them and

no legal recourse until she separated from him. Partly as a result of

her newspaper columns about what she called "the wrongs of womanhood,"

legislators passed a bill in 1847 that gave wives certain rights over

their inherited property and allowed them to write wills. According to

Nichols, this was the first inkling of women’s legal existence in

Vermont.

It took more than 40 years for married women to gain

full access to their personal property, earnings, and custodial rights

to their children, but long held beliefs about women’s legal

incapacities persisted into the 20th century. Women were not allowed to

serve on juries, for example, until 1943. Legal reforms in the 1970s and

1980s, such as no-fault divorce, equitable division of marital

property, and custody rules based upon the best interest of a minor

child, further diminished gender-based inequities. Subtle forms of

discrimination in employment, inequitable pay, and sexual harassment

remain difficult to adjudicate, but Clarina Nichols would be pleased

that women are no longer legally dead.