(HOST) As Vermonters read To Kill A Mockingbird, commentator Tom Slayton, reflects on one event in the 1960s that put Vermont’s racial

(HOST) As Vermonters read To Kill A Mockingbird, commentator Tom Slayton, reflects on one event in the 1960s that put Vermont’s racial

tensions in the national spotlight.

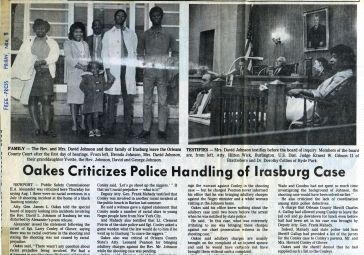

(SLAYTON) The tangled sequence of events that came to be known as "The Irasburg Affair" began July 19, 1968, with a racial attack on the home of a black Baptist minister named David Lee Johnson who had recently moved to Irasburg. Shots were fired at his home late at night from a speeding car.

No one was injured, but the event had strong echoes of southern racist vigilante activities, and alerted Vermont to a distressing truth, one we had tried to ignore: racism – race hatred, actually – existed in our state.

Just how deep those despicable feelings ran  and where they would be found would shock all of Vermont before the Irasburg Affair ended.

and where they would be found would shock all of Vermont before the Irasburg Affair ended.

Immediately after the shooting, the Vermont State Police were assigned to guard Rev. Johnson’s home. But it became apparent that the police had become more interested in investigating David Johnson than in protecting him. They abruptly arrested him and a white woman who had been staying at the house on charges of adultery. A state police trooper said he had witnessed the two engaging in sex.

That shifted the focus of the case from the initial crime – the drive-by shooting at Johnson’s home – to Johnson’s own character and behavior. And it looked suspiciously as though the state police had moved slowly on the shooting case and pretty quickly on the adultery charges.

Suddenly, Vermont was in the national limelight – in a way that no Vermonter had ever wanted the state to be. Was clean little, green little Vermont a hotbed of racial hatred – up to and including those who should be enforcing the law? The national press corps descended upon Orleans County, and a formal Board of Inquiry was appointed by Gov. Philip H. Hoff.

Eventually Larry Conley of Glover was charged with breach of the peace in connection with the shooting. He pled no contest. The adultery charges against Johnson were dropped after the woman involved left the state and refused to return. She pleaded no contest and paid a fine, even though Johnson’s wife testified that no adultery had taken place because Johnson had been with her at the time of the alleged incident. And, given the turmoil surrounding them, it wasn’t surprising when the Johnson family subsequently moved away from Vermont.

It was a sad and inconclusive ending to a sad chapter in Vermont’s history.

The Irasburg affair proved, once again, that despite Vermont’s reputation for friendly acceptance, despite the state’s much-vaunted heroic participation in the Civil War, there is a dark side to our rural life. It was expressed in the last century by the sudden flourishing of the Ku Klux Klan here, and it is expressed now in racial incidents directed against blacks, Muslims, gays – anyone, really, whom the hate-mongers decide is different and somehow threatening.

The Irasburg Affair, and other instances of Vermont’s own home-grown brand of intolerance are worth remembering, if only to remind ourselves that evil can grow anywhere it is allowed to grow – and it must be opposed, even here, in our own the quiet hills and villages.