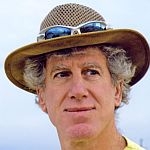

(Host) A number of years ago, naturalist and commentator Ted Levin was

(Host) A number of years ago, naturalist and commentator Ted Levin was

passing through Miami International Airport, when he encountered an

unexpected reminder of home.

(Levin) I was headed home to Vermont

when a chatty skycap asked me if I knew Ben Kilham, from Lyme, New

Hampshire. I told him I did. Then, from the kiosk the skycap pulled out a

well-worn copy of Kilham’s book Among the Bears, and said, "I want to

raise orphan bear cubs too and set them free."

I must admit the congestion in front of the American Airlines desk made the back woods of Lyme seem pretty good to me, too.

I

visited Kilham again recently, after a long, slow drive into the

hinterlands beyond the Dartmouth Skiway. At the time, he was caring for

twenty-seven orphaned cubs – twenty in an eight-acre enclosure and seven

in a bear barn. The cubs in the enclosure arrived nearly a year ago and

had to be bottle-fed. Those in the bear barn arrived this past October

and are still getting used to life as orphans.

To help them

adjust, a playful Massachusetts cub named Slothy serves as an ursine

ambassador. "She gets the traumatized cubs to relax," Kilham told me, as

we sat at the dining room table, observing a fidgety cub by bear-cam,

one of six surveillance cameras that feed images to his i-pad.

Over

the years, Kilham has discovered that black bears are not solitary

mammals, loners that divvy up the woodland resources and cautiously

avoid each other. To the contrary, he says they’re quite social. They

only appear solitary relative to the food supply. If food is abundant,

bears follow a quite elaborate social system.

Bears may have

expressive faces, but like dogs, they read the world mostly with their

noses. They leave olfactory messages throughout the forest. They also

scratch the soft bark of red pines, turn over rocks, and rub tufts of

fur onto tree trunks, all of which has meaning to other bears. It’s been

common practice for bear rehabilitators to try to minimize human

contact with orphaned cubs, but not Ben Kilham.

The idea that

even if a bear doesn’t see you, you are always making contact, is the

essence of Kilham’s rehabilitation. He bonds with the cubs.

He

walks them in the woods, leads them to appropriate food sources, and

essentially becomes their substitute mother. To get to know him, the

tiniest cubs stick their tongues in his mouth.

I wondered if

they would be attracted to people when he released them, but Kilham

doesn’t think so. "No," he says. "You’re not going to walk up and hug a

stranger… You’re not going to get the same signals from the stranger

you’d get from a close friend."

Recently, China asked Kilham to

teach their scientists how to prepare captive-bred panda cubs for

release into the wild. When I asked him if pandas are harder to work

with than black bears, Kilham replied that a bear is a bear.

And Ben

Kilham ought to know.