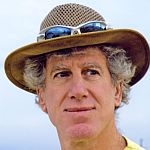

(HOST) For a while now, commentator Ted Levin has been raking up more than leaves.

(HOST) For a while now, commentator Ted Levin has been raking up more than leaves.

(LEVIN) Lately, red oak acorns have attacked our standing-seam roof, tumbling down into the backyard, collecting below the clothesline. Day and night oaks drop nutritious packages of protein and fat, in a sleep-depriving metallic downpour like prairie hail. I’ve raked up more than a bushel and a half; yet still, every morning, the ground is cobbled with acorns. Hanging laundry now requires footwear.

Red oak acorns take two years to mature and every three to five years, depending on a wide variety of variables including weather, geography, genetics, and tree health, Vermont woodlands produce a bumper crop. Before I raked, there was more than a dozen per square foot below the clothesline; a couple of number-crunching biologists tallied nearly 100,000 per acre in western Pennsylvania last fall.

Whenever acorns flood a forest animals prosper, a phenomenon known as a trophic cascade. The summer after acorn over-abundance, the population of white-footed mice and chipmunks, for instance, may swell from one or two per acre to more than a fifty. In fact, with a bumper-crop of red oak acorns, white-footed mice breed straight through the winter. Two years after the acorns, and a year behind the chipmunk and mouse peak, timber rattlesnake births are often much higher.

Recently, I watched a four-foot long rattlesnake on a ridge not far from the Lake Champlain narrows. The snake had unspooled himself at the base of a bitternut hickory, head and neck pointed upward against the trunk as though contemplating heaven. Half-eaten hickory nuts peppered the ground, and the snake, keyed to the subtlest vibration, the subtlest odor, the subtlest increase in infrared heat, waited with the patience of Job for a hungry chipmunk or mouse to descend the trunk.

This scene will repeat itself next summer throughout the lower Champlain valley as endangered rattlesnakes (and milk snakes and black rat snakes) cull seed-eating rodents, whose own bonanza will be a product of this fall’s astronomical acorn crop.

Red oak acorns germinate in spring.

In addition to fat and protein, they’re loaded with tannin, a bitter compound used to cure leather that happens to bind protein and prevent assimilation across the gut wall in seed predators. Rain and snow-melt leach tannin, however, making red oak acorns progressively tastier the longer they remain on the forest floor. Anyway, by early spring, there is often little else left to eat.

I chewed a couple up the other day and I don’t recommend them. They’re both bland and acidic like an oily aspirin. White-tailed deer don’t share my lack of appreciation. Their saliva denatures tannin, rendering red oak acorns immediately palatable. Black bears love them too, as well as blue jay, grackle, wild turkey, fisher and raccoon. Even gray fox. This winter everybody will be satisfied. You might even say – stuffed.

There are three hundred species of oak in North America; sixty north of Mexico; one in my backyard. To hang the laundry I need more than footwear; I need a hardhat.